Who is Atlas Shrugged for?

The ego boost for everyone that convinces no one.

I picked up Atlas Shrugged from the shelf of the used bookstore for the sole reason that the title is undeniably riveting. A simple two word phrase evoking so much mystery and intrigue that I couldn’t pass it up.

As I flipped through the pages, idly reading a line or two to get a sense for the writing style, I reached back in my memory for high school English class where I had read Anthem.

What was that book about? I couldn’t quite remember, but I think it had something to do with ego. We and I. Something like that.

A sucker for books that are probably longer than needed but look impressive on a bookshelf, I plopped the worn copy of Atlas Shrugged – with those wonderfully yellowing pages and creased spine – into my cart and kept moving.

For the next few months it sat at the base of a stack of books. The thousand page length that felt motivating in the bookstore now felt daunting. But finally I picked it up and braced myself for this tome with the irresistible title.

I had no idea what I had in store.

I quickly learned that the plot of this book was not in service of itself. It is not a story about Dagny (the main character) or Hank (her ally) or any of the other dozens of characters. No, the plot and the characters and the world all play a simple role: mouthpiece for Ayn Rand to talk about her philosophy.

Now, I will stop here to say that this essay is not going to make any judgments on that philosophy. If you want that, google “Atlas Shrugged Review” and you will be inundated with opinions of every variety imaginable.

In case you, like me, had heard of Atlas Shrugged, but didn’t know what the fuss was about or what the content of Ayn Rand’s philosophy was, here’s a simplified rundown of the subject and the debate around it:

Atlas Shrugged calls for the vilification of the word need.

Need, to Rand, is the great evil corrupting the world. Other dangerous words include want, give, mercy, and, of course, the public good.

Words of virtue, to Rand, include selfish, earn, produce, and free.

The rallying cry of the heroes of the story goes like this:

“I swear by my life and my love for it that I will never live for the sake of another man, nor ask another man to live for mine.”

And who are these heroes?

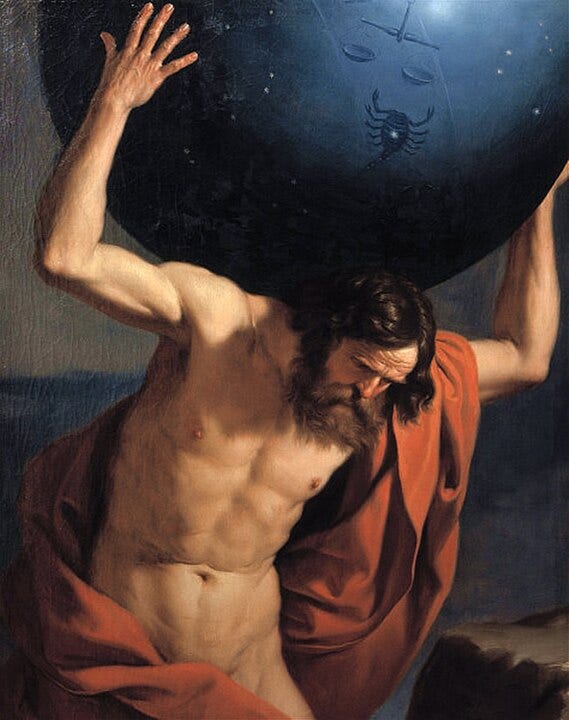

Business titans. Those that make society function by means of their superior intellect and drive to succeed. They are owners of the railroads, the mines, and the steel manufacturing plants.

They are, to Rand, the Atlas holding up the earth, unthanked and ridiculed for the work they do and the beliefs they hold.

Their central belief is in reason. The greatest word in the English language to a believer in Rand’s philosophy. A person who lives by reason denies that they are responsible to the needs of others. They reject the notion that the public good should come above their own. They bristle at the suggestion that mercy is a virtue, and turn instead to the reasoned hand of justice.

Now, in the context of the world of Atlas Shrugged, Hank (a steel titan) has just invented a new type of steel – Rearden Steel – that is stronger and lighter and more efficient than anything the world has ever seen.

It was going to launch the world into a frenzied state of progress the likes of which it hadn’t seen since the industrial revolution.

But instead, the government steps in, takes claim of the steel for the public good, and attempts – with little success – to manage it.

This sets off a series of events that ends with all the business titans leaving the world behind. They hide in the mountains, cut off from society. They let the dull masses reap what they’ve sown.

The Atlas’s of Rand’s world have shrugged and walked away.

In their absence, left to the devices of the corrupt of Washington and the incompetent remaining businessmen, the world falls apart.

The heroes of the story watch from afar, awaiting the day the world burns completely to the ground, so that they may return and rebuild from the ashes.

So, that’s the gist.

You may be wondering, if I’m not going to cast my judgment on the philosophy of this book, then what is the point of this essay?

Well, thanks for asking, I’ll tell you.

My question is this:

Who is Atlas Shrugged for?

Honestly, what is the target audience?

This is the epitome of a “love it or hate it?” kind of book. Read for ten minutes online and you will see people saying they reread it every year and base their life choices off its ideas, and others say their eyes were burning with every word they read they hated it so much.

And so here is my problem – the rhetoric is not effective for anyone.

If you already believe in the regulation-free, laissez-faire capitalist, virtuous selfishness world idealized in this story, you will lap up this story as gospel and gladly preach it to the masses.

But, if you disagree, you’ll roll your eyes so far into the back of your head that you’ll never see straight again and you’ll shout into the gaping holes in logic left by Rand, listening with delight as the echoes chant their support of your worldview.

So, who is actually being challenged by this book? Who is having their beliefs shifted? Who actually changes their mind about anything after reading this book?

There are two main reasons the rhetoric of Rand falls short.

First, the strawman arguments.

Everybody knows that if you wish to truly defeat an opposing ideology, you must face the best of what they have to offer.

If you beat Dickey Simpkins off the ‘96 Bulls roster in 1-on-1, and then proclaimed you’d beaten Phil Jackson’s record breaking team, everyone would laugh you off the court.

What about Michael Jordan and Scottie Pippen? You’ve haven’t beaten the Bulls, just the worst the Bulls had to offer.

That is what Rand does in her story.

The bad guys of the story – those hawking the virtue of the public good, of mercy, of regulation – are all blubbering fools. They can barely string a cohesive sentence together, they are unfailingly corrupt and they are self-serving (which would actually impress Rand in other circumstances).

Their go-to catch phrases are whiny cries of “It couldn’t be helped!” “It’s not my fault!” or “I never said that!”

They fall to the pull of their vices, they fill the emptiness of their lives with petty grievances and joyless luxury. They are miserable, scheming people with no redeeming qualities.

A lover of Rand might be pumping their fist and cheering along to these descriptions. Yes! They might say, See how dumb they are! We’re smart!

But this kind of argument only works in the made-up world of Rand’s book where every person who opposes the business titans is a weak, unintelligent fool.

In the real world, where there is intellect to be found wherever you look (yes, even on the side of people you disagree with), this argument falls apart.

Rand enjoyed the luxury of never having to answer a difficult question, because the characters she created never asked them.

Each time a titan hero gave a speech, the dull masses were struck into silence or else raved on with their “It couldn’t be helped!” pleas.

None gave a rebuttal. None challenged the beliefs of Rand. None pushed back in any effective way.

And this is to Rand’s detriment!

If her goal in writing this book was to illustrate the effectiveness and correctness of her worldview, she should have put it to the greatest test possible. She should have challenged it from every side to prove how strong the argument was.

Instead she insulated it from any challenge and therefore gave no evidence of its merit.

The second failing of rhetoric is much like the first, but inverted.

The steelman arguments for her own side.

While every person opposing Rand is cast as a fool, every hero from her story is an idealized being, incapable or error.

Each of these titans are essentially the same character with a different industry tacked on (steel, rail, copper, etc.). They all live by a code (live only for yourself, ask no one to live for you) and never, ever break from it.

They are prone to no moral shortcomings, no slip-ups, no botched words or second-guessing.

They say and do exactly what they proclaim to believe at every moment of their lives.

No person in the history of the world has lived perfectly within their morals. Yet in Ayn Rand’s story, everyone who agrees with her does 100% of the time.

The only time there is a suggestion of moral failure – an affair that Hank has with fellow titan Dagny – it is revealed later, much to Hank’s relief, that it actually wasn’t a moral failure at all. It was right that he cheated on his dull wife because he deserved it, and she deserved nothing.

Many have made the argument that the whole premise of the story is defunct because if every person acted as consistently in their morals as Rand has her characters act, then any social system would work.

The issue with all these systems is that people are inconsistent, unpredictable, and uncontrollable. Life is not so clean cut as Rand makes it out to be on paper.

Again, this choice to smooth out any imperfection from her protagonists is to her own detriment!

To argue effectively for her cause, she should have had at least a couple heroes show weakness. She should have shown how her system could be corrupted by imperfect people, and then illustrate the ways it would defend itself.

Instead, Rand chooses to reside comfortably in a fantasy of her own making, convincing no one but herself.

There are two ways I think Rand could have improved her arguments, to at least make it challenging to read, instead of eliciting only eye-rolls or thoughtless cheers.

First, Dr. Robert Stadler.

In the story, this character is the representation of moral failure. He knew better – he understood Rand’s philosophy – but he fell away.

This is fine, but it could have been better.

Rand decided to have Dr. Stadler fall into the ways of the enemy, and then spend the rest of the book whining about it and feeling guilty.

Here’s a different approach I wish she had taken:

Have Dr. Stadler fall away from Rand’s philosophy, then join the other side with the intellect and power and strength that Rand already admitted he was capable of.

Give the opposition a hero of their own, a worthy foe.

Let him lead the defenders of the public good against the defenders of selfishness.

Let him be their champion, so that the reader sees a true argument on the pages, not the pointless, spineless shouting of Rand’s philosophy through her chosen mouthpieces.

The second and final thing Rand could have done to improve the rhetoric of her book is to make Eddie Willers into something more.

Eddie Willers, for those who haven’t read the book, is a man dedicated to the ideals of Rand. He is loyal to the titans of industry, but he is not one himself. He is a common man. He does not have the skills to be a titan of industry.

And because of this, he is left behind.

In the most emotionally resonant moment in the book, Eddie is trapped in the middle of nowhere with a stalled train that he can’t – no matter how he tries – get to start again.

It’s the summation of Rand’s ideas. The titans are gone (they are hiding in the mountains) and those left behind can’t get the motor of the world started again. Without Atlas, the world falls.

Rand wanted to show how helpless we were without her heroes, but she is saying something else too.

She is saying that those like Eddie, who believed in this system and these morals, are nonetheless punished for their lack of ability. That Eddie and those like him are fundamentally less than the titans hiding in the mountains, and Rand’s philosophy (being anti-mercy) unfeelingly leaves them behind.

In short: if you don’t have ability, tough luck, you’re getting left behind.

This doesn’t hold up to much scrutiny.

Would Dagny (the titan of the railroad) have been able to start that train by herself?

I would argue no, since earlier in the book she was in a similar situation and couldn’t. She instead got in a plane and literally flew away, leaving the train stranded. Clearly the ability to start a train is not required for Dagny, so why was it damning for Eddie?

Now, here is where Rand could have made things interesting.

Dagny loved Eddie, relied on him, confided in him. And yet she leaves him behind.

Does she feel remorse? Likely not, but I would have loved to explore it. How does Dagny feel about the fruits of a philosophy that leaves a loyal, dedicated man to the wolves?

This could have been a moment for Dagny to question her own philosophy, to truly look it in the eyes and understand the consequences. Is Eddie a sacrifice to Rand’s philosophy? Maybe so. But we aren’t given the time to consider this question because the characters never do.

More importantly though, Rand never addresses a gaping hole in her logic.

Dagny was born the daughter of the previous railroad titan. She was raised in incredible wealth. She was given exclusive access and insight into the railroad that is impossible for others to attain. She was given an elite education. She was given a family name that carried weight and opened doors.

That is a lot of giving for a philosophy that considers that word a sin.

What if Eddie had been born in her shoes?

Would he then have been capable of being a titan? Would he then have been invited into the secret mountain hideout?

If so, then what is truly the merit of a titan like Dagny?

When your philosophy is based on asking for nothing of your fellow men, and yet your place of power is partially the result of your reliance on your family name and the benefits and boosts that position gave you, your argument that Eddie doesn’t deserve a spot by your side is hypocritical.

Rand, unsurprisingly, ignores all of this nuance in favor of her clean-cut, blinders-on vision of the world.

Whether or not Rand’s worldview is correct is not really a question you can answer after reading this book, because it’s not one Rand asks.

She tells. She rants and raves. She demands you see the world her way, yet declines to give any good reasons why. She turns from the slightest indication of resistance and constructs a fantasy world where everything she believes goes unchallenged.

I saw a review of this book that said it’s like the conversations you have with yourself in the shower. The ones where you are arguing with a friend or spouse and everything you say is perfect and devastating and undeniable. In your head, what you think is the only possible thing to think. It is fact carved into stone.

Then you step out of the shower and go speak to that person, ready to give them the moral beatdown of a lifetime, and then they ask a simple question that throws your shower-monologue to the wind and challenges everything you thought was so obvious when hidden in the protective bubble of your own mind.

Ayn Rand, in Atlas Shrugged, is comfortable in the safety of her own mind. She casts moral judgments at others, but scurries away from even the hint of a rebuttal.

If you’re looking for a book that will challenge your beliefs, this won’t satisfy.

If you’re looking to feel morally superior (whether in your agreement or disagreement) this is the perfect book.

I greatly appreciate the time and effort you took to read Atlas Shrugged, then to write about it. About 15 years ago I read it and thought about it a lot. I think you absolutely captured its weaknesses. Well done!

What I most agree with you about is how one dimensional I found the characters to be. It’s so obvious that they are all there to prove Rand’s point...maybe all books are like that. But I never noticed more than here. Just one dissenting hero and maybe I would have liked it more lol