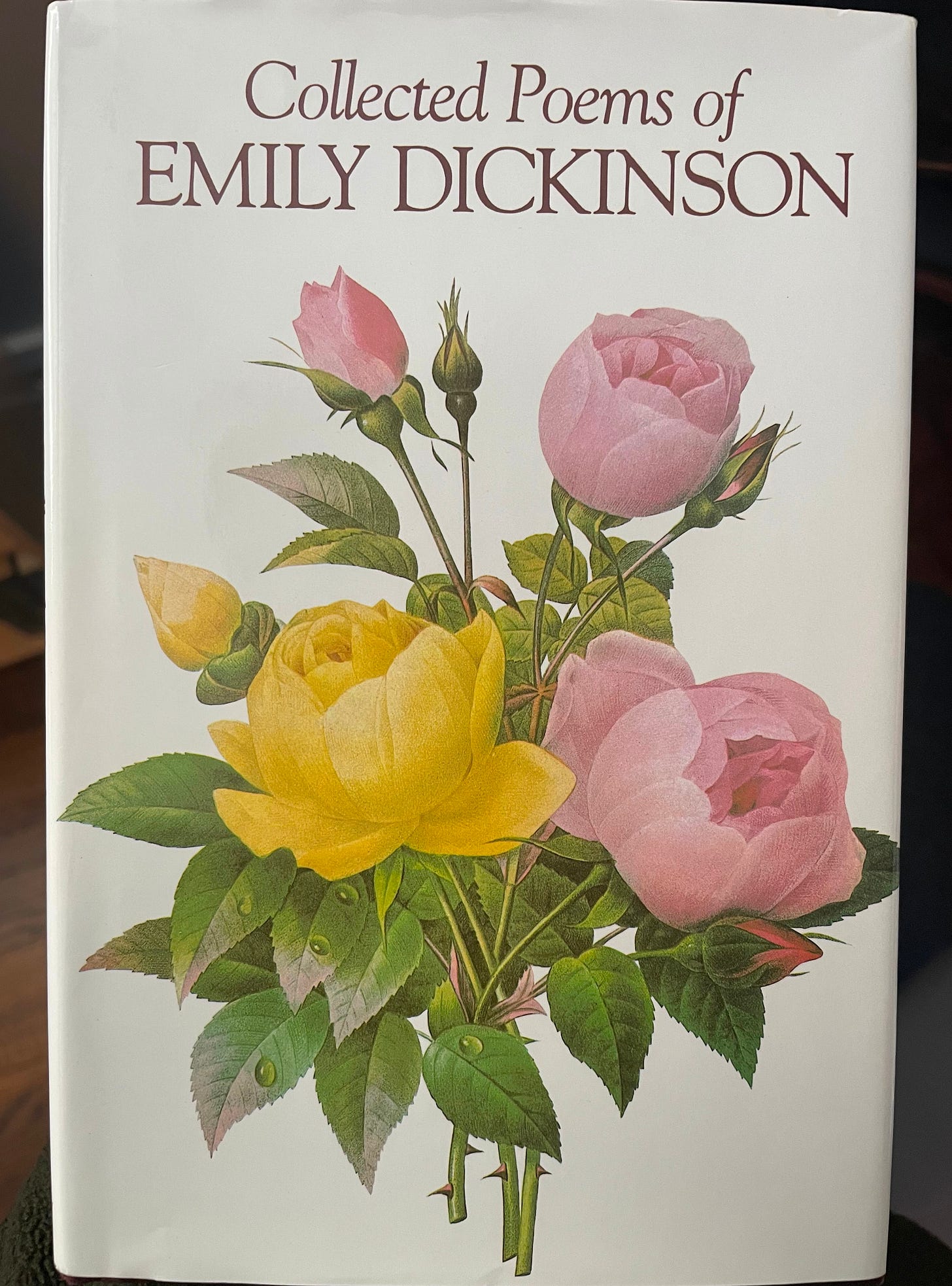

I’ve just finished reading the above pictured collection of Emily Dickinson poems, which served as my first attempt to focus on poetry for a sustained period of time and see if this elusive medium can become something more concrete for me. Before this, poetry had always been the thing I read when assigned in high school English classes or college creative writing courses. I remember being drawn in each time. The teachers and professors would explain the depth of a poem that I couldn’t see on my own and this process of revelation through study was exciting. The idea that the same collection of words can mean next to nothing on first pass, but increase in meaning with each re-read was enough to make me want to explore poetry further. But, this enthusiasm would fade quickly after class. I would try to read on my own, but without the classroom environment to help me parcel out meaning, I usually gave up the effort and retreated to reliable prose.

This time, though, I was determined to push through the discomfort. The strategy was simple: keep reading, even when it doesn’t make sense. I reminded myself of the way I read Shakespeare in high school (where without internet summaries I would have been lost), to the way I read it now that I’m used to the style of language. Poetry was just another style of language I’d have to get accustomed to.

So, with that strategy in mind, I slowly, over the course of several months, worked my way through Collected Poems of Emily Dickinson. I knew nothing about Dickinson’s life as I was reading apart from that which is common knowledge: she was more famous as a recluse than a poet and nearly all her work was published posthumously. This had a massive effect on how I read her poems. I often wondered about her point of view on religion, happiness, family, and the like, but had only her poetry to provide answers. At some point in the future I will read a Dickinson biography and return to these poems with more context.

Below are some takeaways from my reading experience:

First, nature poetry puts me to sleep. I had an incredibly hard time connecting with it. For every poem that struck me with its beautiful or unique ways of describing nature, there were five that elicited no response. I am more intrigued by descriptions of nature when they are in service of some greater goal. In prose this is often creating a feeling of place, of worldbuilding, and of mood setting. In other poetry it’s in the service of metaphor. But poetry that simply describes the beauty or feeling of a season or natural location does nothing for me. This was informative for my future endeavors into poets outside of Dickinson. I may never do a deep dive on the famous nature poets, however renowned.

Second, I thought a lot about the circumstances in which Dickinson wrote these poems. Again, I know little about her life, but I did read this from the introduction from 1890 by Thomas Wentworth Higginson:

“The verses of Emily Dickinson belong emphatically to what Emerson long since called “the Poetry of the Portfolio,” – something produced absolutely without the thought of publication, and solely by way of expression of the writer’s own mind. Such verse must inevitably forfeit whatever advantage lies in the discipline of public criticism and the enforced conformity to accepted ways. On the other hand, it may often gain something through the habit of freedom and unconventional utterance of daring thoughts. In the case of the present author, there was absolutely no choice in the matter; she must write thus, or not at all.”

From this information it seems Dickinson was truly writing for herself, at least most of the time. I wonder how many poems that are now featured in collections were jotted down hastily before a meal then left in some drawer and forgotten, until it was collected after her death and placed side by side with the poems she worked on tirelessly for days and days. Without her there to vet the polished poems from the raw ones, we are left to guess. This is part of why I am so curious to learn her opinions about faith and death and all the big questions of life, because she may have been writing these poems to discover her thoughts about these questions, not to declare them. How much of what she wrote was the feeling of a moment versus a steady conviction?

Now, at the end of my reading, I want to share the poems that stood out to me in various categories.

DEATH

Apparently with no surprise

To any happy flower,

The frost beheads it at its play

In accidental power.

.

The blond assassin passes on,

The sun proceeds unmoved

To measure off another day

For an approved God.

Happiness comes to those who understand the scarcity of their days, and yet play. The world is not spiteful in cutting us down. Things just happen. Life just ends. And the sun marches on at its set pace.

This poem feels in line with the idea that the way to live best is to get comfortable with the reality of our death.

So proud she was to die

It made us all ashamed

That what we cherished, so unknown

To her desire seemed

.

So satisfied to go

Where none of us should be,

Immediately, that anguish stooped

Almost to jealousy.

One of the darkest in the collection. She feels a dark jealousy for those who die. She feels a strange embarassment for clinging to life while the one dying, with their newfound perspective, no longer count life as worth clinging to. In the end though, she declaires death the place none should go. And I think the description of her jealousy as stooping is important.

THE PAST

The past is such a curious creature,

To look her in the face

A transport may reward us,

Or a disgrace

.

Unarmed if any meet her,

I charge him, fly!

Her rusty ammunition

Might yet reply!

Dickinson had a couple poems about the past, and guilt, that stood out to me. The first was interesting because though the past may reward us (and bring happy memories), it is still wise to run from it for fear of the pain that might come should the past remind us of something less flattering.

I years had been from home,

And now, before the door,

I dared not open, lest a face

I never saw before

.

Stare vacant into mine

And ask my business there

My business, – just a life I left,

Was such still dwelling there?

While reading I especially enjoyed when Dickinson inserted a small narrative into her poems, like this one. It talks about a return, and the fear that comes along with it. Will things be the same? Is what I left behind even available to me anymore?

Remorse is memory awake,

Her companies astir

A presence of departed acts

At window and at door

.

It’s past set down before the soul

And lighted with a match

Perusal to facilitate

Of its condense dispatch

.

Remorse is cureless, – the disease

Not even God can heal;

For it is his institution,--

The complement of hell.

I include this one mostly for the line “It’s past set down before the soul and lighted with a match.” That description of remorse is poignant and has stuck with me since I read it months ago.

LOVE

If you were coming in the Fall,

I'd brush the Summer by

With half a smile, and half a spurn,

As Housewives do, a Fly.

.

If I could see you in a year,

I'd wind the months in balls

And put them each in separate Drawers,

For fear the numbers fuse

.

If only Centuries, delayed,

I'd count them on my Hand,

Subtracting, til my fingers dropped

Into Van Dieman's Land,

.

If certain, when this life was out

That yours and mine, should be

I'd toss it yonder, like a Rind,

And taste Eternity

.

But, now, uncertain of the length

Of this, that is between,

It goads me, like the Goblin Bee

That will not state its sting.

First thing I like about this is that I recently read a book about the history of Australia, so the reference to Van Diemen’s land (Tasmania) was a fun easter egg.

This was my favorite of the love poems by far. Any amount of time apart is bearable, except that unknown amount. Beautiful.

DESIRE

Undue significance a starving man attaches to food

Far off; he sighs, and therefore hopeless, and therefore good.

Partaken, it relieves indeed, but proves us that spices fly

In the receipt. It was the distance was savory

A running theme in Dickinson poetry is that the longing for a thing is better than the thing itself. Distance from your desires is the true sweetness. My uneducated asumption is that her desire is to be recognized for her work. But then again, maybe not. Maybe she truly wrote for herself. If that’s the case, then what was this desire(s) that she longed for so much, but really hoped to never reach?

Who never wanted, – maddest joy

Remains to him unknown;

The banquet of abstemiousness

Surpasses that of wine.

.

Within its hope, though yet ungrasped

Desire’s perfect goal,

No nearer, lest reality

Should disentrall thy soul

In the game of desire, the true winners are the losers. Why? Because success and accomplishment bring reality, whereas longing remains in the blissful imagination. Always out of reach, and therefore never fully in the light of day. Never fully examined. Never dissapointing.

Success is counted sweetest

By those who ne’er succeed

To comprehend a nectar

Requires sorest need.

.

Not one of all the purple host

Who took the flag to-day

Can tell the definition,

So clear, of victory,

.

As he, defeated, dying,

On whose forbidden ear

The distant strains of triumph

Break, agonizing and clear.

The same idea as the previous poems, but I love the imagry of the man who lies dying on the battlefield, cruelly within earshot of the celebratory victors.

PAIN

Pain has an element of blank;

It cannot recollect

When it began, or if there were

A day when it was not

.

It has not future but itself,

Its infinite realms contain

Its past, enlightened to perceive

New periods of pain

When we are in the throws of pain, the future and the past dissolve. There is only the present, terrible moment.

For each ecstatic instant

We must an anguish pay

In keen and quivering ratio

To the Ecstasy.

.

For each beloved hour

Sharp pittances of years,

Bitter contested farthings

And coffers heaped with tears.

This poem is interesting because it becomes more despodent as it goes on. The first stanza seems to say that each good thing is balanced by a bad, but the second says that an hour of goodness is repayed by years.

They say that ‘time assuages,’-

Time never did assuage;

An actual suffering strengthens,

As sinews do, with age.

.

Time is a test of trouble,

But not a remedy.

If such it prove, it prove too

There was no malady

Suffering, to Dickinson, does not ease with time but grows stronger. If the suffering is real, it will not fade.

MISC

We never know we go, – when we are going

We jest and shut the door;

Fate following behind us bolts it,

And we accost no more.

I love this one. Short, easy to understand, and yet still powerful. We make these choices everyday and then suddenly the door slams and our fate has hold of us. We can’t go back.

I’m nobody! Who are you?

Are you nobody, too?

Then there’s a pair of us – don’t tell!

They’d banish us, you know.

.

How dreary to be somebody!

How public, like a frog

To tell your name the livelong day

To an admiring bog!

This feels to me like a case of unreliable narrator. She praises being “nobody” and keeping that fact a secret. But her true fear is being banished. She calls society a “bog” but is afriad of being cast from it.

I many times thought peace had come,

When peace was far away;

As wrecked men deem they sight the land

At centre of the sea,

.

And struggle slacker, but to prove,

As hopelessly as I,

How many fictitious shores

Before the harbor lie

What we think is the finish line is often not. The things we think will bring us peace, if we can just reach them, don’t, and another finish line materializes in the far distance.

One need not be a chamber—to be haunted—

One need not be a House—

The Brain—has Corridors surpassing

Material Place—

.

Far safer, of a Midnight—meeting

External Ghost—

Than an Interior—confronting—

That cooler—Host—

.

Far safer, through an Abbey—gallop—

The Stones a’chase—

Than moonless—One’s A’self encounter—

In lonesome place—

.

Ourself—behind Ourself—Concealed—

Should startle—most—

Assassin—hid in Our Apartment—

Be Horror’s least—

.

The Prudent—carries a Revolver—

He bolts the Door,

O’erlooking a Superior Spectre

More near—

Don’t be afriad of the world, be afriad of yourself. We’ve got haunted houses right inside our skulls. Dickinson’s advice? Bolt the door and carry a revoler for use against the spectre most near…

One final section, a side by side comparison of Dickinson’s contradicting takes on hope.

HOPE

“Hope” is the thing with feathers -

That perches in the soul -

And sings the tune without the words -

And never stops - at all -

.

And sweetest - in the Gale - is heard -

And sore must be the storm -

That could abash the little Bird

That kept so many warm -

.

I’ve heard it in the chillest land -

And on the strangest Sea -

Yet - never - in Extremity,

It asked a crumb - of me.

The first is the positive take. Hope perches in the soul and its song is sweet to hear. It keeps us warm. I asks nothing of us. It simply abides with us, through every storm.

Hope is a subtle Glutton —

He feeds upon the Fair —

And yet — inspected closely

What Abstinence is there —

.

His is the Halcyon Table —

That never seats but One —

And whatsoever is consumed

The same amount remain —

And here’s her darker take on hope. Hope feeds on the fair.

One way to read the second stanza is that hope itself sits at the table and consumes and consumes. It is never satisfied. No amount gained stops hope from wanting more.

A gentler take is that the perspetive shifts in this second stanza and actually hope is setting the table for us. No matter how much hope we go through, there is always more available.

And that’s it! My experience reading Emily Dickinson. I can’t wait to get started on the next poet (I’m thinking Keats right now, but we’ll see).

Thanks for reading.